Notes from Prof. Gregory Scheckler: last updated 2023.

The idea that nature consists of groupings of changing processes is deeply cultural, and personal, as well as evidential and scientific and universal. Time is often experienced as change, proceeding moment by moment, or as a perpetual flow of events into the future, recalled via dream-like memories, and predicted by tuning into reliable repeating patterns. Nested within those concepts of time are the ancient words of Heraclitus of Ephesus:

“One cannot step twice into the same river, nor can one grasp any mortal substance in a stable condition, but it scatters and again gathers; it forms and dissolves, and approaches and departs.”

– Heraclitus (Kahn translation)

Written at around 500 B.C.E., that sense of dynamic change in nature was contemporary with the works of Lao Tzu, and those of the Buddha. Heraclitus proposed a universal sensibility, called panta rhei, meaning ‘everything flows.’

This claim stood in contrast to Parmenides’ competing belief in an unchanging eternal reality, and also in contrast to Plato’s dualism separating ideas as eternal forms that may have their own logic outside of nature. In Renaissance art, inspired often by Platonic dualist idealism (read: classicism and its idealizations of form), the concept of a changing never-ending istoria infused the composition of interchangeable panels in religious altarpieces that could be opened and closed according to the seasons. Although they responded to time as changing seasons, such trends in some European cultures emphasized unchanging eternal ideas (the supernatural, conceived of as existing outside of the natural). This created a core collaboration and conflict among monism (philosophical naturalism) versus dualism (philosophical idealism). This conflict-collaboration courses through a lot of contemporary American culture today.

For example, time and it’s conception in contemporary art overlaps with cultural intersections that emphasized various types of time as change, especially through the Zen Buddhist lectures and writings of Daisetz Suzuki. He popularized Zen in the first half of the 20th Century, and along with several others (Alan Watts, for example) he attracted experimental artists. This was followed closely by Shunryu Suzuki’s writings, which also emphasized transience. Transience is the conception of change through time’s processions. Many abstract painting methods, and a great deal of experimental music, stemmed from interactions with either or both Suzuki. Artists like Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Mitchell focused through nature imagery and founded new art methods for abstraction inspired in part by these teachings. Another artist of the same era who created time-based abstractions was Cy Twombly, through his experiences (like many abstract painters) at the Black Mountain College, where composer John Cage taught his famous Zen-influenced presentations “Lecture on Something” and “Lecture on Nothing” and “Indeterminacy.” As focal points for abstract painters, these lectures reflected key concepts from Zen such as indeterminacy and transience, selflessness and being through time. In America, sometimes the translations of Zen concepts through the Beat Generation of poets, was called ‘Beat Zen,’ a somewhat simplified and less ritualistic form of Zen than that taught in Japan.

In the sciences, we see similar reflections of these conflicting concepts of time too, used in varying proportions for useful equations. I lean heavily toward contemporary science’s monist view (philosophical naturalism), especially as the sciences intensify and clarify the qualities of these changing processes in nature: the universe’s expansion contrasted by the pull of gravity and push of radiation, how continents shift as plate tectonics, how evolution produces species, cycles of molecular feedback in microbiology, how fleeting subatomic microcosms operate as shifting, rising and collapsing waves. These can be reduced to the Standard Model in physics, of four main forces (gravity, electromagnetism, and the two main nuclear forces), interacting through time and movement, describing and predicting how matter, energy, form and function interrelate.

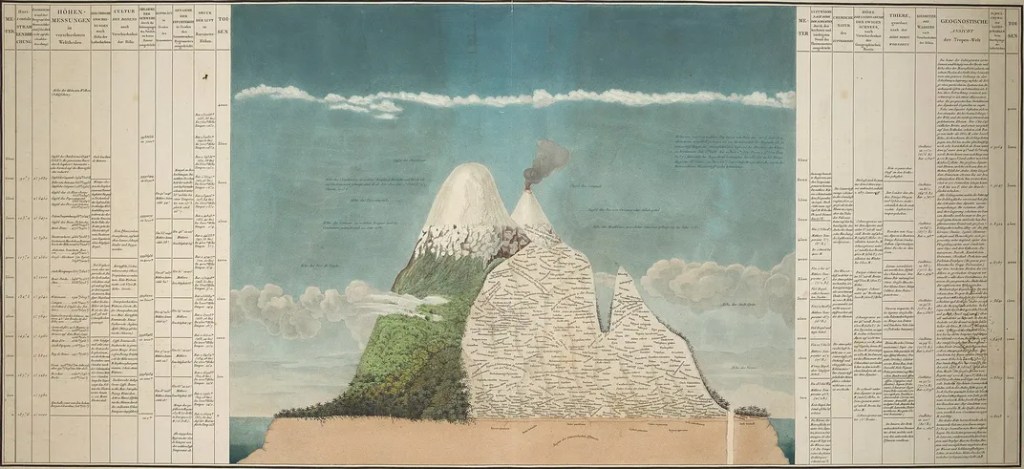

In ecology and nature writing, the sense of interrelationships as processes of nature became more culturally prominent in Europe by the 18th Century, as early scientist-explorer-poets like Alexander von Humboldt formed new ideas that emphasized the older German phrase Naturgemälde. This word literally means ‘nature’s painting,’ but figuratively implied a global unity of nature and intellect and feeling, and thus a return to a new kind of monism – that there is nothing other than nature, which is beautiful and which can be considered both as science and art, intellect and feeling, all on its own. It can also be carefully measured. These ideas also stemmed from the then-popular Romanticist movement, that combined emotion and intellect through the arts and sciences. Humboldt travelled the world making intensive measurements of climate, air, plant life, and much more, discerned over vast timespans across his many journeys:

Humboldt’s accomplishments formed early ecology, relating climate to botany to human activity, and even inspiring some early understandings of humanity’s affect on climate and ecology – inspiring Darwin and Thoreau. Naturgemälde echoes in Darwin’s famous ending of On the Origin of Species that recognizes simpler dynamic forces combining to result in nature’s diversity:

“… to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms… have all been produced by laws acting around us… whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

The beautiful balancing of many scientific equations point to a dynamic cosmos within which we are both embedded and participant. Excellent introductions to the main concepts of these balancing relationships in contemporary sciences are the popular explanations such as Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time (Bantam: 1988), which puts the idea of an expanding, dynamic universe into contexts of modern physics and their histories. This has been updated recently in Leonard Mlodinow’s A Briefer History of Time (Bantam: 2005). I agree with physicist Frank Wilczek’s suggestion, in his book Fundamentals: Ten Keys to Reality (Penguin: 2021), that the ramifications of the many sciences can be uncomfortable but that also “When we see ourselves as patterns in matter, it is natural to draw our circle of kinship very wide indeed.” That becomes a type of ecological thinking of our relationships with the world. Unlike the separations reinforced by various dualist philosophies, the core monist philosophies and their histories supporting the contemporary sciences point to our inclusion within nature, through vivid descriptions of nature as a dynamic suite of fundamental physical forces interacting with each other in time, or from which time results. This sense of sequencing can be measured to incredible precision and accuracy today, unlocking many discoveries.

As an artist, these concepts and cultures are personal to me as well. First and foremost, my own cultural background is punctual German-American, religious, and reflective of many of these concepts of early ecology and the sciences. My parents are both Catholics and highly trained scientists, and my mother later became a professional musician. They both led nature hikes in a state park in northern Wisconsin, teaching me (and many others) basics of plant identification, natural history, geology, and so on. We usually had science-oriented guidebooks and conversations around the home, including of Humboldt, Darwin, and many nature writers like Thoreau, Leopold, and Sigurd Olsen. Early in my college education I pursued engineering, taking courses in physics, calculus, thermodynamics and so on — but later shifted over to art studies, during which I wrote about the similarities and differences among art and science. Meanwhile, rebelling against my parents’ religiosity, I attended Zen meditation weekly in the early 1990’s while I was also in art school. This provided an intercultural overlap with Zen ideas and experiences, which infused a lot of 20th-Century art. I felt like a cultural outsider looking in on Zen’s beauty and creativity, but have also felt that the secular, meditational-philosophical aspects of Zen can be very useful. They are also grounded in their own type of naturalism, as distinct from other types of Buddhism. The scale and descriptions of nature, as processes working together and against each other, is quite different across these varying scientific and cultural viewpoints, but they all tend to point to nature as dynamic in time, arising and fading away together, balancing, sometimes conflicting and sometimes collaborating. Related back to art-making, I think that my own personal relationships with these cultures inspires me to adopt a sparse aesthetic, one that is responsive to ideas of change in time, as well as to using materials and methods in process-oriented, ecological, environmentally-friendly ways.

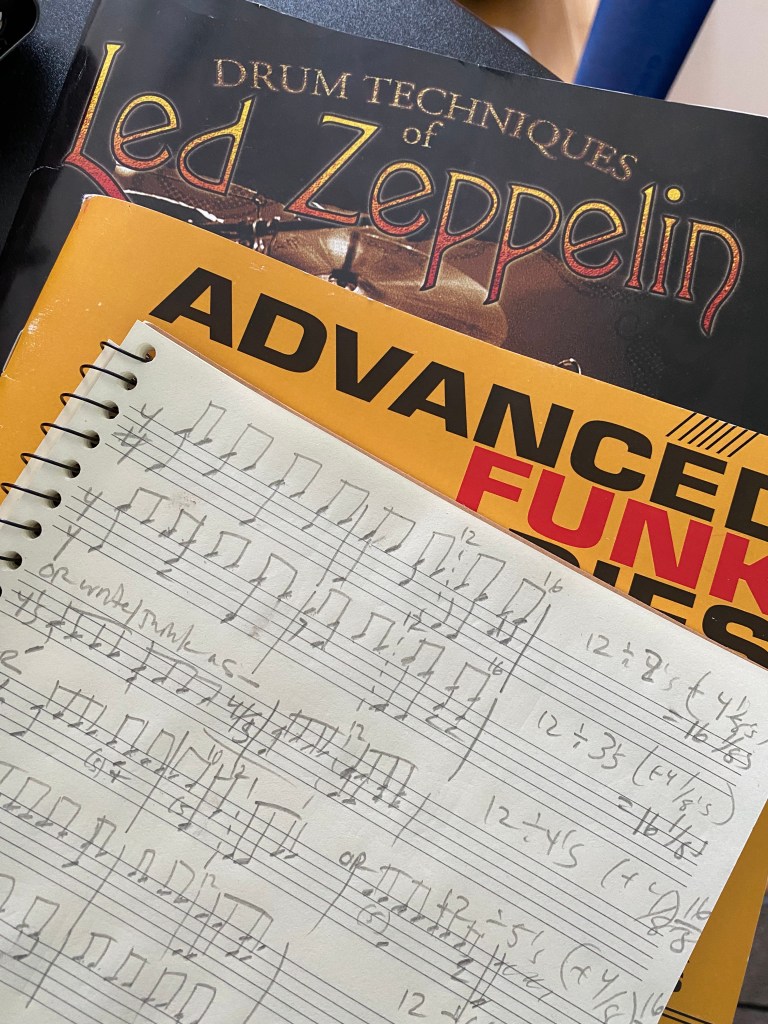

Another fundamental piece of considering time and timing is contemporary music, and its relationships to encoding and measuring varying concepts of time’s passage. I started playing drums in my youth, and continue to do so today — on this I’ll write more later, but basically it’s a great joy, in which one is not so much ‘keeping time’ as ‘being time’ while also subdividing it into the flow of various numeric rudiments and patterns. Music automatically rises and fades in time, and is often considered as a temporary and performative art form, in contrast to a lot of fine art painting, that is sometimes thought of as archival or permanent, unchanging and to be viewed (rather than performed). I’ve worked against that concept of painting, and toward a more music-like approach in time applied to visual art.

And as far as drawing is concerned, these conflicts and collaborations are also evidenced in the main ideas of concrete, specific point-of-view illusions and representations of figurative art traditions that hold an image still and thus emphasize several dualist ways of thinking (such as contour drawing, linear perspective, constructive drawing and mass/tonal drawing) versus art traditions that respond to movement and action in time as a more monist approach (such as gesture drawing, abstract action-drawing, some kinds of algorithmic or procedural drawing, or some forms of drawing for animation). Many drawings combine some of both sets of approaches.

To ‘be in the moment’, by the way, is perhaps a strange aspiration, because you already are in it, and of it. This is a fundamental reflection of contemporary ecological thinking: we are part and participant in the world, influenced by it while also affecting it. Rather than separated from nature, we are embedded and interrelated and part of nature, time, and so more. Reinforcing that ecological togetherness and belonging seems to me to be an important need in contemporary art and society.

Sources / Further reading:

The Art and Thought of Heraclitus, p. 53, by Charles Kahn, Cambridge University Press: 1987

The Discovery of Pictorial Composition: Theories of Visual Order in Painting, 1400-1800, by Thomas Puttfarken, Yale: 2000

Essays in Zen Buddhism, by D. T. Suzuki, Souvenir Press: 1927, reprinted 2020

The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860–1989, exhibit catalog ed. by Alexandra Munroe, Guggenheim Museum: 2009, and featuring works by Mary Cassatt, Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, Jack Kerouac and many others…

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki, Shambhala: 2020, 50th anniversary edition

Silence: Lectures and Writings, John Cage, Wesleyan: 1961

Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler – Five Painters and the Movement that Changed Modern Art, by Mary Gabriel, Back Bay Books: 2018

The Invention of Nature: the Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt the Lost Hero of Science, by Andrea Wulf, Vintage:2016

On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin: 1859

A Brief History of Time Stephen Hawking, Bantam: 1988

A Briefer History of Time Leonard Mlodinow, Bantam: 2005

Fundamentals: Ten Keys to Reality, Frank Wilczek, p.226, Penguin: 2021